In my last post on using Perseus in upper level language courses, I talked a lot about consulting the dictionary entry for various words. In today’s post, I’m going to talk about all the wonderful information found in a dictionary entry and explain how to find the appropriate definition for your word.

Dictionary Rundown

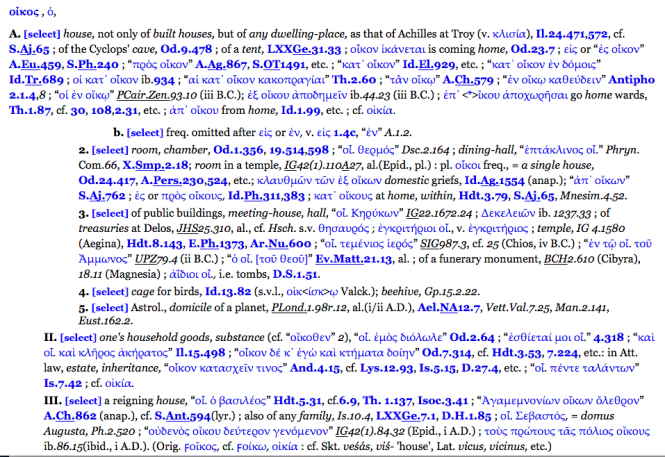

I already talked about choosing a dictionary in a previous post. The size of the dictionary is going to dictate how detailed the entry is. As an example, here is a comparison between the entry for the Greek word οἶκος in the ‘Middle’ Liddell (the intermediate-sized Greek dictionary) and the LSJ (the largest size of Greek dictionary).

Or so it seems until you compare the LSJ!

You can see that the entry in the LSJ is roughly three times as long as the one in the ‘Middle’ Liddell. The largest difference is the number of examples of the word being used with various meanings. For a noun as simple as οἶκος, this might not seem that important — but it’s really useful when you come across (for example) verbs that have different and/or complex meanings in the middle voice.

In some cases, the passages that you are reading might even be listed in the LSJ as an example of usage. For example, in Herodotus 1.2:

Notice the verb ἄρξαι in the second line. Clicking on the verb brings up the LSJ entry:

TIP: the citation always follows the Greek.

You can see that this specific passage is used as an example for one of the primary meanings of ἄρχω: “make a beginning of.”And you also learn that it takes the genitive, which can help you locate its object.

Sometimes using the larger dictionary entry can be distracting and can cause confusion, especially for students in lower-level courses. (In fact, Jackie used her trusty ‘Middle’ Liddell well into graduate school.) Most of the time, the entry in the Elementary Lewis or the ‘Middle’ Liddell is more than enough information and you can almost forget entirely about the larger dictionaries if a longer entry causes undue anxiety. The upside to the longer entry, however, is more examples and a better understanding of what the word means. Obviously, if you are using a hard copy, you’ll use the dictionary you have on hand (and there is nothing wrong with that, especially considering the cost of large Latin and Greek dictionaries) but if you are using Perseus and you have access to both entries, it’s usually worth at least a peak at the longer one. If you struggle to understand the entries in the LSJ, perhaps look first at the entry in the ‘Middle’ Liddell first to get a basic roadmap for what the word means. That can help you understand the longer, more complex LSJ entries.

While I do think it’s important to always use the biggest dictionary you can get your hands on, there is something to be said here about Homeric Dictionaries. When reading Homer, it is often just as good, if not better, to use a Homeric Dictionary (like the Autenrieth) instead of the LSJ or the ‘Middle’ Liddell. Some words have very specific meanings in Homer that are different from their later, classical meanings. Using a Homeric dictionary can ensure that you are finding the right meaning of the word. As a caveat, you should always make sure that you remember that the words you learn the Homeric meaning for can have different most common meanings in other/later dialects of Greek and different forms. The best practice might be to use the LSJ and a Homeric dictionary side-by-side so that you can contrast the meanings between them and learn them both at the same time.

The entry in detail

There is a lot of information inside a dictionary entry, so let’s take a close look at some examples. First up is a very simple Latin noun, the word villa.

First is the nominative singular (the form that you use to look it up), followed by an alternate spelling for a “rustic” form found in Varro in parentheses. The Lewis and Short will often provide alternate or archaic spellings for words to help you out if you are reading an older text. The probable origin of the word is also given. Next you’ll notice that the genitive singular ending –ae is given, along with the gender (f.) of the noun. These three parts — nominative singular, genitive singular, and gender — form the dictionary entry. The dictionary entry gives you enough information to decline or conjugate any word in full. In this case, it tells you that villa is a 1st-declension feminine noun. The word itself means, very simply, ‘country house’, and examples are provided to show that it can mean a country house in general, or very specific houses like the Villa Publica on the Campus Martius.

Taking a look at a more complicated entry, here is the entry for the Greek adjective μυρίος in the LSJ:

The adjective μυρίος, as you can see, is usually a regular 1st/2nd declension adjective of three endings. BUT sometimes it’s used as an adjective of two endings — something that could really throw you off if you didn’t know about it. It means most basically “numberless, countless, infinite”, which you might have guessed if you know the word myriad. Note, however, that there are some interesting tidbits in this entry. First, although μυρίος is typically used in the plural, it can be used in the singular to modify collective nouns (examples are given). It can also be used in the neuter plural OR in the dative as an adverb. Furthermore, μυρίος also has a very specific meaning, “ten thousand”, that’s very common in military contexts. Also note that the final entry, Roman numeral III, tells you that the word takes on a different accentuation in later Greek.

Takeaway

The most important part of using the dictionary is reading the entry and recognizing what kinds of information the entry contains. The dictionary will give you the tools to decline or conjugate a word, suggest where the word comes from, and provide archaic or alternate spellings when they exist. Most importantly, the dictionary tells you how the word is used and what its meanings are. Most words (even simple nouns like villa) have more than one meaning, and using a comprehensive dictionary (like the ‘Middle’ Liddell or LSJ for Greek and the Elementary Lewis or Lewis and Short for Latin) will give you the best idea of what the word means. These dictionaries are very expensive in hard copy, but they are online for free on Perseus in a handy, searchable format. For those of you who like a paper dictionary, there are other options too; I mentioned some of them in the first post in this series. The most important point to remember is that by an upper-level reading course, you need more than the vocab list at the back of your textbook.

I would recommend always reading the complete dictionary entry for a word you are unfamiliar with to see if the word makes sense in your particular case with one of its more specific or obscure meanings. If none of the indicators that the word might mean something out of the ordinary are there, it’s usually best to stick with the entries that are closer to the outside (so the ones with capital letters or Roman numerals).

Dictionary work, like everything else in studying ancient languages, improves the more often you do it. I would recommend getting familiar with the larger dictionaries as early as possible, starting in lower-level reading courses so that you are ready for action once you get into your third or fourth year.

~M.

[…] this series on surviving upper level language courses, we’ve covered expectations, dictionaries, and how to use Perseus. Today we’ll take a look at what to do when you’re languages […]

LikeLike

[…] had a few posts on how important your dictionary skills are to your language success, and we’ve even told you some of our […]

LikeLike

[…] will create up to 100 for longer texts. I really like this particular flashcard feature. Students taking Latin courses will find it particularly useful, I think, because they can study the vocabulary that is most […]

LikeLike